Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

Women's Rights & Issues

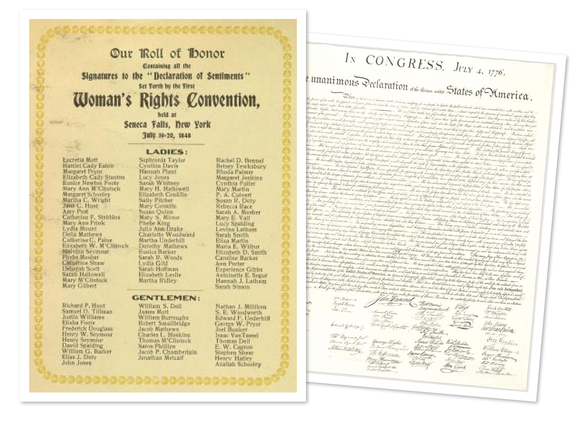

Related: About this forumThe Women's Rights Convention, Seneca Falls, 19-20 July 1848

“The First Wave” statue exhibit in the lobby of the Women’s Rights National Historical Park visitor center in Seneca Falls, NY.

Women's Rights National Historical Park New York

https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/report-of-the-womans-rights-convention.htm

Seneca Falls Convention

This mahogany tea table was used on July 16, 1848, to compose much of the first draft of the Declaration of Sentiments.

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women's rights convention.[1] It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman".[2] Held in Seneca Falls, New York, it spanned two days over July 19–20, 1848. Attracting widespread attention, it was soon followed by other women's rights conventions, including one in Rochester, New York, two weeks later. In 1850 the first in a series of annual National Women's Rights Conventions met in Worcester, Massachusetts. Female Quakers local to the area organized the meeting along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who was not a Quaker. They planned the event during a visit to the area by Philadelphia-based Lucretia Mott. Mott, a Quaker, was famous for her oratorical ability, which was rare during an era in which women were often not allowed to speak in public.

The meeting comprised six sessions including a lecture on law, a humorous presentation, and multiple discussions about the role of women in society. Stanton and the Quaker women presented two prepared documents, the Declaration of Sentiments and an accompanying list of resolutions, to be debated and modified before being put forward for signatures. A heated debate sprang up regarding women's right to vote, with many – including Mott – urging the removal of this concept, but Frederick Douglass, who was the convention's sole African American attendee, argued eloquently for its inclusion, and the suffrage resolution was retained. Exactly 100 of approximately 300 attendees signed the document, mostly women.

The convention was seen by some of its contemporaries, including featured speaker Mott, as one important step among many others in the continuing effort by women to gain for themselves a greater proportion of social, civil and moral rights,[3] while it was viewed by others as a revolutionary beginning to the struggle by women for complete equality with men. Stanton considered the Seneca Falls Convention to be the beginning of the women's rights movement, an opinion that was echoed in the History of Woman Suffrage, which Stanton co-wrote.[3]

The convention's Declaration of Sentiments became "the single most important factor in spreading news of the women's rights movement around the country in 1848 and into the future", according to Judith Wellman, a historian of the convention.[4] By the time of the National Women's Rights Convention of 1851, the issue of women's right to vote had become a central tenet of the United States women's rights movement.[5] These conventions became annual events until the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861.

. . . . .

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seneca_Falls_Convention

5 Things You May Not Know About the Seneca Falls Convention:

July 19-20 marks the anniversary of the Women’s Rights Convention, a.k.a., the Seneca Falls Convention. This two-day convention held in Seneca Falls, New York in 1848 is hailed as the first women’s rights convention. Over 300 men and women gathered together to “discuss the social, civil and religious rights and condition of woman.” Notable reformers were present, such as Frederick Douglass. It launched the national career of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. And it set into motion events and relationships that would forever change American society. Here are five things you may not know about the convention:

1. More People Signed the Declaration of Sentiments than the Declaration of Independence

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and members of Mary Ann M’Clintock’s family drafted the Declaration of Sentiments, modeled after the Deceleration of Independence. Like its inspiration, it outlined the injustices women faced and put forth 11 resolutions the convention adopted that were crucial to women realizing equality in American life. The ninth resolution, the most famous, was that women deserved and should seek the vote. 100 people signed the Declaration of Sentiments. The Declaration of Independence had 56 signatures.

. . . . .

Amelia Bloomer was another national figure at Seneca Falls. She was famous for her work in the Dress Reform movement and educating women about the physical dangers of Victorian clothing. She is also responsible for creating one of the most celebrated female partnerships in American history by introducing Elizabeth Cady Stanton to Susan B. Anthony, who also wore the Bloomer Fashion for a short period of time. Amelia Bloomer did not sign the Declaration of Sentiments. Some believe this is because she thought it would detract from the Temperance Movement. In her biography of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, historian Elizabeth Griffith states there is even doubt that Amelia Bloomer actually attended the meeting.

The bloomer costume. Lithograph by N. Currier, 1851.

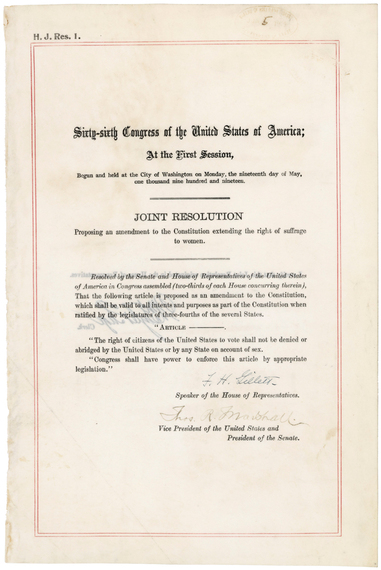

4. Only One Signer of the Declaration of Sentiments Lived to see the Passage of the 19th Amendment

Charlotte Woodward Pierce was 18 or 19 when she was at the Seneca Falls Convention. Of the 68 women who signed, she was the only one who lived to 1920 when the 19th Amendment was passed. Not much is known about her life. She was teaching by the age of 15 but also doing domestic and sewing work as well. She was in her early 90s when women won the right to vote and donated a trowel to the National Women’s Party in 1921 as they broke ground on their new headquarters. Sadly, she never actually voted. She was ill and confined to her bed on Election Day in 1920.

19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Women’s Right to Vote.

. . . . . .

Declaration of Sentiments Water Wall at the Women’s Rights National Historical Park.

. . . . . .

InfoView thread info, including edit history

TrashPut this thread in your Trash Can (My DU » Trash Can)

BookmarkAdd this thread to your Bookmarks (My DU » Bookmarks)

0 replies, 1372 views

ShareGet links to this post and/or share on social media

AlertAlert this post for a rule violation

PowersThere are no powers you can use on this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

ReplyReply to this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

Rec (3)

ReplyReply to this post