Science

Related: About this forumDid a genetic mutation lead to a woman being convicted of murdering her four children?

Here's an interesting article in Nature News Feature I came across today:

She was convicted of killing her four children. Could a gene mutation set her free?

Subtitle:

Some excerpts:

“I’ve had three SIDS deaths already,” she explained, referring to sudden infant death syndrome — a largely unexplained phenomenon that typically affects infants in their first year, as they sleep.

Around 9 p.m. that night, pathologist Allan Cala conducted an autopsy on the baby, named Laura, at the New South Wales Institute of Forensic Medicine in Glebe, a suburb of Sydney. In his report, he noted no evidence of injury and no medications, drugs or alcohol in her system. He mentioned some inflammation of the heart, possibly caused by a virus, but surmised that it could be incidental. Instead, Cala opined on the improbability of four children in the same family dying from SIDS. “The possibility of multiple homicides in this family has not been excluded,” the report stated.

Four years later, in May 2003, a jury found Folbigg guilty of murdering three of her children — Patrick, Sarah and Laura — and of the manslaughter of her first son, Caleb. Because there were no physical signs of foul play in any of the deaths, the case had rested entirely on circumstantial evidence, including the unlikelihood of four unexplained deaths occurring in one household. Lightning doesn’t strike the same person four times, the prosecutor told the jury.

Folbigg was sentenced to 40 years in prison, and became known as Australia’s worst female serial killer. But in 2018, a group of scientists began gathering evidence that suggested another possibility for the deaths — that at least two of them were attributable to a genetic mutation that can affect heart function. A judicial inquiry in 2019 failed to reverse Folbigg’s conviction, but this month, the researchers will present a bolus of new evidence at a second inquiry, which could ultimately end in freedom for Folbigg after nearly 20 years behind bars. More than 90 scientists signed a March 2021 petition arguing for her release on the basis of that evidence.

The inquiry will have to grapple with how science weighs the evidence for genetic causes of disease, and how that fits with the legal system’s concept of reasonable doubt. But it will have help. Thomas Bathurst, the retired judge leading the inquiry who will decide Folbigg’s fate, has granted permission for the Australian Academy of Science in Canberra to act as an independent scientific adviser. The academy will recommend experts to give evidence, and will look at questions asked of those experts to ensure their scientific accuracy.

This will probably present the science more accurately than at the original trial, says Jason Chin, a legal academic at the University of Sydney who studies the way science is used in courts. And this case could have implications for how Australian legal proceedings consider scientific evidence in other cases, says Chin.

Sudden suspicion

Folbigg’s four children died over a period of ten years. Caleb was just 19 days old in 1989 at the time of his death. Patrick and Sarah were 8 and 10 months old, respectively. Soon after Laura’s death, Folbigg was placed under suspicion and eventually stood trial in a case that became a dramatic public spectacle. At the time, multiple SIDS deaths in a single family were viewed with suspicion, particularly against mothers.

That suspicion traces at least in part to Roy Meadow, a British paediatrician who studied child abuse. In 1997, he popularized the idea that “one sudden infant death is a tragedy, two is suspicious and three is murder, unless proven otherwise”. At Folbigg’s trial, this line of thinking clearly influenced some experts’ testimony...

Meadow's claim was already under suspicion:

After Ms Folbigg has spent 19 years in prison, a possible genetic cause of the children's deaths is now being considered:

As part of their preparations for the inquiry, Folbigg’s lawyers approached Carola Vinuesa, a geneticist at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra at the time, to sequence and analyse Folbigg’s DNA. The idea was to see whether she carried any mutations that, if inherited by the children, might offer an alternative explanation for how they died. Vinuesa agreed to help. Her colleague, Todor Arsov, a geneticist who lived in Sydney, travelled to the nearby Silverwater Women’s Correctional Centre, where Folbigg was being held, to collect a sample from her.

That December, Arsov joined Vinuesa in her kitchen to scroll through sequence data looking for variants linked to sudden death. Within 20 minutes, they both came across something interesting: a variant in a gene called calmodulin 2 (CALM2).

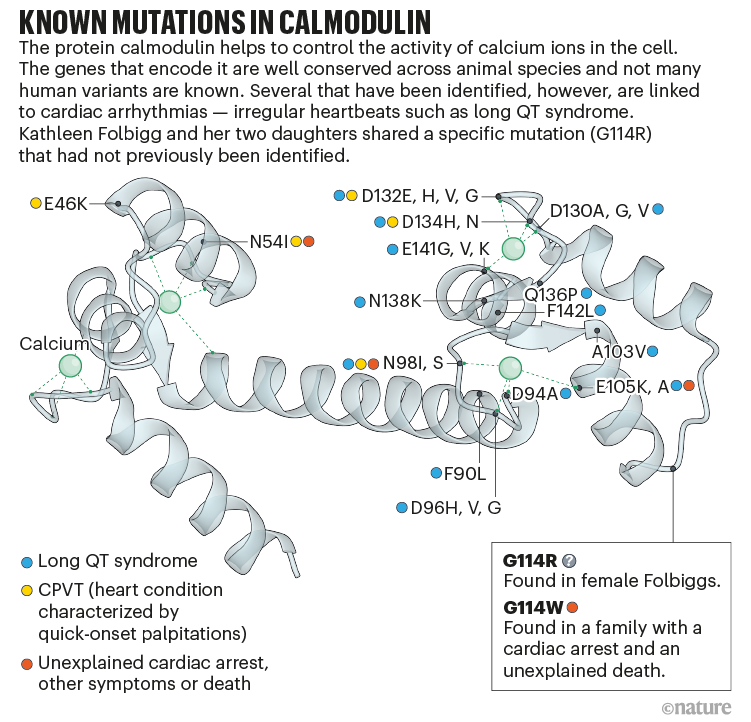

Humans have three calmodulin genes, encoding identical proteins that bind to calcium and control its concentration in cells, which helps to regulate the heart’s contractions, among other things. Mutations in these genes are extremely rare, but people who have them often have serious cardiac conditions; sudden deaths have been reported. Vinuesa thought the find was worth further investigation. She suggested to Folbigg’s lawyers that they attempt to sequence DNA from the children and their father...

The children's tissues have been sequenced, but not that of the children's father:

Apparently the calmodulin gene is highly conserved, most mammals have an identical sequence to that of humans. This implies that mutations in the gene cannot be tolerated, that the expressed protein is not functional with modifications, and thus the gene does not evolve as other genes do.

Ms. Folbigg and her deceased children have a variant called G114R, where the 114th amino acid residue glycine (G) is replaced with arginine (R).

After the first inquiry, Vinuesa e-mailed Overgaard and asked whether he could perform a functional assay to determine the cellular effects of the Folbigg variant. Overgaard wasn’t familiar with the case, but was drawn to the idea of seeing “another piece in the puzzle to try and figure out how calmodulin works”, he says.

Overgaard asked postdocs Helene Halkjær Jensen and Malene Brohus to do the lab work. Everything about the project was secretive: even other researchers in their lab didn’t know about it. “We had a folder on our computer called CSI,” says Jensen, a reference to the popular US television drama about crime-scene investigators.

Jensen and Brohus spent weeks painstakingly making calmodulin proteins with the Folbigg mutation, known as G114R, in which the amino acid glycine (G) at the 114th position of the protein is replaced with an arginine (R). For comparison, they created proteins with two other calmodulin variants known to cause severe arrhythmias, G114W and N98S (see ‘Known mutations in calmodulin’).

It is known that certain mutations in calmodulin lead to heart diseases, notably arrhythmias.

A figure from the article:

For that they asked Dick, who studies the protein CaV1.2, a channel that shepherds calcium into the cell. Calmodulin triggers this channel to close once enough calcium has entered. Overgaard asked Dick to look specifically at whether the mutation impaired the closure of CaV1.2. Dick had never heard of the Folbigg case, but to prevent her team from introducing any bias, she relabelled dishes of cells to hide their provenance. Sure enough, the Folbigg variant delayed the channel closure, letting extra calcium into the cell. “That’s what we know to be one of the signatures of a pathogenic calmodulin mutation,” Dick says.

But that wasn’t the only effect the variant had. Wayne Chen, who studies calcium channels at the University of Calgary in Canada, was asked to conduct similar experiments on a ryanodine receptor, a channel that controls the release of calcium into the cell from intracellular stores. As it does with CaV1.2, calmodulin binds to ryanodine receptors and triggers the channels to close. This prompts the heart muscle to relax. When Chen’s team expressed the G114R variant in human cells, that channel had trouble closing, too. The combined effect of the variant on both channels will increase calcium in the cell, says Dick, which increases the chance of arrhythmia. “If you asked me, ‘Would this mutation be likely to cause sudden death?’, I would say somebody with this mutation is at very high risk of that,” she says...

For now Ms. Folbigg remains in prison, based on the circumstantial evidence that all four of her children dying couldn't be a coincidence.

If the cause of the children's death turns out to be genetic, a great injustice will have been done.

Hugh_Lebowski

(33,643 posts)"The children's tissues have been sequenced, but not that of the children's father"

That lack of the sequencing for the father seems like a rather critical piece of missing info.

Unless this problem is known (or at least thought) to be 100% maternal in terms of how it's passed, you really need to know that piece.

And then there's the question ... are these her only 4 children?

Does she have others that have lived?

NNadir

(33,624 posts)It's not necessarily the case that the father needed to have the gene. In any case, the article says that he supported the prosecution of his wife. It would seem very unlikely that he would have this mutation. It's extremely rare, probably because it's often fatal. It was not fatal to Ms. Folbigg herself, which is a strong caveat to the case which is discussed in the article, but there are cases of disease genes not necessarily producing symptoms of the disease. It may be more of a risk to children than to adults; perhaps some people having this gene will survive it long enough for some effects, possibly maturity itself, leading to physiological amelioration of the risk of death.

Even some recessive genes have health effects. In the case of Sickle Cell Anemia, people carrying a single recessive allele do not have sickle cell disease, but they are immune to malaria.

A dominant disease gene is apparently the case in Jimmy Carter's family, where both of his parents and all of his siblings died from pancreatic cancer. (His mother Lillian, lived to a fairly old age however.). I would assume he inherited the double recessive gene and thus did not get pancreatic cancer. I know at some point I looked this gene up, but I've forgotten what it was.

Hugh_Lebowski

(33,643 posts)just a genetically-based occurrence ... if 1 or 2 or 3 of 4 her kids had died very young of similar causes, vs 4/4 of them.

An ex-girlfriend of mine just passed of Huntington's a couple weeks ago, at 50. Her mom and 2 older brothers had passed of the same genetic defect before her, clearly mom was the carrier, as dad is fine. But her other sibling, a sister, is unaffected.

3 of 4 seems to me like the limit for something like this before I'm not thinking to myself ... wow, that's some very bad luck, to the point where I wonder about 'other reasons'.

It's surely possible, akin to flipping heads 4 times in a row. But strikes me as pretty unlikely is all.

NNadir

(33,624 posts)...on the jury, and were I to have the evidence described in the Nature article, I would have held out adamantly for acquittal, using, at least the standard of "reasonable doubt." In this case, I think, it would be unreasonable, extremely so, not to doubt guilt. In fact, I strongly suspect that this woman is innocent.

Of course, the prosecution to advance their case, would almost certainly use a challenge to keep me off the jury, if this evidence, not available at the time of the trial, were offered in discovery, since I actually know something about proteomics.

This is a previously unknown mutation, G114R, and specifically it involves a change for a neutral, very small amino acid, one which in effect has no side chain, glycine, for highly charged amino acid, with a very large side chain, arginine. As is mentioned in the article it is known that a similar substitution, at residue 114, G114W (glycine substituted by tryptophan) led to fatal events.

The tertiary structure of proteins, the feature that controls their operability, is very much controlled by charges on side chains. In fact, turning proteins "on and off" is generally controlled by varying side chain charges. In particular, the class of compounds known as "kinases" control physiology - sometimes causing it to go haywire as in cancer - by phosphorylating or de-phosphorylating amino acids with hydroxy side chains (serine and threonine and even sometimes tyrosine).

The calmodulin protein is highly conserved across vertebrae species, meaning that it doesn't take much to make it dysfunctional. We do not know whether the children all have this mutation, but it is hardly statistically impossible for them to do so, about 1 in 16. The reason that this gene is previously unknown may well be that it is almost always fatal in children, that is, natural selection prevents people having the mutation from living long enough to have children.

This begs the question of why Ms. Folbigg, who has the mutation, has survived long enough to have children. A possible answer to my thinking, is the realization that proteins do not function in an isolated environment. They interact with one another strongly, often in a long chain of events. Although arginine is a coded amino acid, it is often post translationally converted to the lysine analogue ornithine via deguanidation while incorporated in the protein.

To satisfy myself that this is entirely possible I entered the following search terms into Google Scholar:

ornithine, arginine, post translational, calmodulin, heart (2,480 hits)

...and, in another search...

ornithine aminotransferase "heart disease" (2,280 hits).

It's entirely possible in my mind that Ms. Folbigg may have had another protein that her children lacked, which served to act on the specific arginine in the G114R mutation (or perhaps another region of the calmodulin protein) making it more functional.

If it is found that the tissues of the children all show the G114R mutation, this woman should be released in my view, and the courts should apologize to her. I note that highly qualified scientists, vastly more knowledgeable than I am, have taken up her cause.

By the way, her former husband is a piece of shit for not offering up his genome for review. Perhaps he's "concerned" he'll look bad for vilifying his wife if she is innocent.

I suspect that Ms Folbigg's biggest crime was having more children after losing the first two. I don't know anything at all about her relationship to her husband, but it strikes me that something was rotten in that marriage.

A piece of circumstantial evidence used against her in her original trial was that she kept a diary noting how difficult it was to deal with the children's crying. I can sympathize. My oldest son had colic, and really didn't stop crying for long periods, until he was about 9 months old. If I or my wife had kept a diary, as Ms. Folbigg did, I'm sure it would have included complaints, perhaps some bitter, which is not to say we didn't love our son; he's 28 now and is a treasured member of our family of whom we are very proud. I note that he had a somatic mutation that led to certain facial difference that was only partially treatable; it never went away fully. It's still there. Fortunately the mutation was not fatal (although in some embryos it is, depending on the timing of when the mutation occurs.)

We were often approached by rude people when he was a baby who wanted to know "what we did" to "cause" that.

Of course I wanted to scream at these people and tell them to go fuck themselves, but I restrained myself, because I did not want my son to live with his gene derived "difference" as a source of stress and anger. I simply said, "we don't know the cause," which was true at the time, although I recently discovered a paper that explained the cause fully.

A pernicious interaction between genes and justice is not a new case. In fact, right up to the current day, injustice has been connected with a single nucleotide polymorphism that a subclass of human beings lack, having failed to become mutants. The mutants thus decided to treat the non-mutants with extreme injustice, a criminal enterprise that persists to this day.

This mutation is described here: Anthony L. Cook, Wei Chen, Amy E. Thurber, Darren J. Smit, Aaron G. Smith, Timothy G. Bladen, Darren L. Brown, David L. Duffy, Lorenza Pastorino, Giovanna Bianchi-Scarra, J. Helen Leonard, Jennifer L. Stow, Richard A. Sturm,

Analysis of Cultured Human Melanocytes Based on Polymorphisms within the SLC45A2/MATP, SLC24A5/NCKX5, and OCA2/P Loci, Journal of Investigative Dermatology, Volume 129, Issue 2, 2009, Pages 392-405.

Hugh_Lebowski

(33,643 posts)Even with my simplistic calculations ... .5 * .5 * .5 * .5 odds are still 6.25% chance of innocence.

I agree it should be enough, were I on a jury, to resist proclaiming this as 'beyond a reasonable doubt'.

I understand SOME doubt/reticence, but in the end, I mean ... how many mothers want to kill their own children? It happens but it's exceptionally rare.

Hope you have a nice weekend ... it's been a surprisingly good week in a lot of ways ![]()

NNadir

(33,624 posts)...even better if in the end we finally hold the Senate and House.

.0625 = (1/2)^4 = 1/16. Certainly a "reasonable doubt."

If she's released - and I think she should be - it would be most interesting to consider her full genome to understand what's going on, why she's still alive. It does seem to me, at least on the superficial level that I operate, that changes to the Calmodulin protein is involved in heart disease and perhaps there is something in her genome that give insight to how to address heart disease.

The case causes me to wonder about my own genome. I have an unusual EKG which often causes doctors to freak out and think I've had a heart attack. I've gone through a myriad of diagnostic tests in connection with it, in the last 30 or 40 years, always with the same conclusion: My heart is fine, rather normal for my age. This conversation has inspired some research into the issue to see if there's anything there.

I've rather settled the issue by getting a CT scan of a new type that images the heart. I told my doctor I don't want to do any tests ever again to diagnose something involving my heart. It's a waste of resources, and I regret authorizing some of the later tests. If, in fact, my heart kills me, I've had a rather long and interesting life, and I have, I think, not totally wasted my time on the planet. Something will get me in any case.

Thanks again for your kind words.

NH Ethylene

(30,840 posts)Your ex gf's sister was lucky. Such a devastating disease.

ratchiweenie

(7,766 posts)NH Ethylene

(30,840 posts)Especially since SIDS has been such a mystery and that there is no reason why congenital defects could not be one of the culprits.